The poem in question: Means To The End

About the time this poem was written, my family took a trip to Oregon, via motor home. I don’t recall if it was the primary purpose, but we visited some extended family there. We also drove through the redwood forest in northern California, where I bought some “happy rocks,” which are little tiny rocks with smiley faces drawn on them.

It was a long drive (I know approximately how long, given that last fall I made a similar drive with my wife and children), but it was nice to have a bit of room to move around in rather than just being crammed into our minivan. As I recall, the old LDS movie Saturday’s Warrior was watched over and over during the drive by my sisters, along with My Girl. I read some books, and I think wrote this poem during or shortly after the trip.

The reason the subject matter was on my mind, I think, is that a shortly before we left, our bishop stopped by for an impromptu interview regarding whether I should be ordained to the Melchizedek Priesthood. In another six months I would be 19 years old and eligible to serve a mission for the LDS church. We had a brief discussion and the bishop told me he would consider things while our family was gone.

Throughout my life, I have often had a difficult time fully relating to things that I could not tangibly experience, though the written word helped me out a lot, in that it was both easy to ingest emotion and to filter out things I didn’t really want to experience. So one of the ways I tried to experience a deeper closeness to the Lord was to write about him from a fictional spectator’s point of view.

The title Means To The End is a mixed bag. It evokes the common phrase “the ends justify the means,” which does not generally carry positive connotations. I suppose I was trying to turn that around somehow. I’m not sure how appropriate it is, but I stand by it.

A man who has been traveling for a while sees Jesus ahead on the road, and looking for some walking company (but not necessarily anything else) speeds up a little to catch him. The first thing out of Jesus’ mouth is that He’d like to be friends. For me, that is the fundamental characteristic of Jesus. Regardless of all the other godly characteristics He may possess, the personal relationship is first and foremost.

The man is a little taken aback by this statement; I just met you and that’s the first thing you say to me? But he’s drawn in by a kind smile. He’s not a sucker; I like to think that when Jesus smiles, you just feel that good. Within just a short amount of time, Christ has been betrayed and is on trial. Despite not knowing Jesus personally for long, the man already knows “no horm could this man ever do.”

Then the scene switches to the Crucifixion. Despite the reworking (and somewhat recontextualizing) of the famous words, “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do” I think the heart of the matter is actually in the middle of the last stanza:

I caught His gaze and saw the passion hidden deep within

And in that moment, He quelled all my fears.

Again, despite the overarching reach of Jesus to be a savior for everyone, the focus for this person is, well, personal. Even though this moment is terrible, he is individually reassured. And that’s what I think Jesus is all about. It is also in this final stanza that the capitalization of pronouns referring to Jesus commences. It’s at this moment of true, personal connection that he becomes Him.

Now, a few words about a different, apparently earlier version of the text. I have one that changes three lines. The first is inconsequential: the last line of the second stanza,”This man would serve them better dead” became “The man would serve them better dead.”

The second is also relatively of little note: near the end of the first stanza, “We set off again, and as we walked…” became “We walked again, and as we walked….” I think the final version flows better.

The third change is the most interesting to me. The lines

I scurried to catch up to him, and so he looked at me

And straightway said he’d like to be my friend.

originally read:

I scurried to catch up to him, and so he looked at me

And told me that he’d like to be my friend.

The change to use of the word straightway was deliberate. The word is used several times in the King James Version of the New Testament, and I take its meaning to be that of suggesting immediacy. The reference I always connect with use of the word is Mark 1:18, where Jesus tells some of the apostles who are fishermen to follow Him, and “straightway they… followed him.” The use in my poem reinforces to me the priority of Jesus to establish a personal friendship with each of us.

Finally, two years later, while serving as a missionary in France, I used this poem as a basis for one I wrote in French to share with members of the Church there. I debated whether to give the text its own blog entry, but I think maybe it fits here. I am pretty proud of the job I did of translation, especially the use of the passé simple tense, which is generally reserved for literary or other written texts. It is not something generally learned in high school French class or as part of missionary language training (but is used in The Book of Mormon and the Bible), so I had to struggle to get it right.

Mon Plus Beau Cadeau

Je rencontrai un homme l’autre jour qui me dit de le suivre.

D’abord, je m’en méfiai, mais il sourit.

J’oubliai toute pensée que ce fût un homme méchant

et sus que par lui je serais nourri.

Il me parla des chose si simples, des choses si évidentes;

je crus que n’importe qui pouvait les faire.

Moi, je n’eus pas l’idée en tête qu’il pût être contredit,

mais, tristement, j’appris le contraire.

Il y en eut certains qui le haïrent, certains qui voulurent le trahir.

Sans preuve de culpabilité ils voulurent voir son sang versé.

Je savais, tout au fond de moi, qu’il n’avait enfreint aucune loi,

mais ils crièrent toujours plus fort: «Il faut que l’homme soit mis à mort!»

Il survécut une nuit d’enfer avant d’être même plus tourmenté.

Sans se dérober, il prit la coupe qui lui fut confiée.

Je regardai son agonie, monté sur sa croix,

versant mes larmes sur cet homme de bien.

Puis je vis la passion qui était dans son regard

et tout à coup, je ne craignis plus rien.

Ses lèvres s’ouvrirent et j’entendis les mots qu’il chuchota:

«Tu vois, O Père, combien j’aime ceux-ci.

Me voici, Fils Bien-Aimé, qui meurs pour tes enfants,

celui qui prie d’épargner ses brebis.»

Quel amour me remplit le cœur en entendant ces mots précieux:

il mourut pour que moi, je vive, en sa presence toujours aux cieux.

The rough English translation of the above text is:

My Most Beautiful Gift

I met a man the other day who told me to follow him.

I didn’t trust him at first, but he smiled.

I abandoned all thought that this was a wicked man

and knew that I would be nourished by him.

He spoke to me of things so simple, so obvious;

I thought anyone could do them.

I couldn’t imagine that he could be contradicted,

but, sadly, I learned otherwise.

There were certain people who hated him, who wanted to betray him.

Without proof of guilt they wanted to see his blood spilled.

I knew, deep down, that he had broken no law,

But they cried louder, “This man must be put to death!”

He survived a night of hell before being tormented even more.

Without shrinking away, he took the cup that was given him.

I watched his agony, mounted on his cross,

spilling my tears over this good man.

Then I saw the passion in his gaze

and suddenly I feared nothing.

His lips opened, and I heard the words he whispered:

“You see, O Father, how much I love these.

Behold me, Beloved Son, who dies for your children,

he who prays to spare his sheep.”

What love filled my heart in hearing these precious words;

he died that I might live in his presence forever in heaven.

Poetism Commentary: “Something Broken”

The poem in question: Something Broken

When I was about 13, my older cousin recommended The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever to me. I probably shouldn’t have read them till I was a little older, but to this day they remain some of my absolute favorite books. The Second Chronicles of Thomas Covenant are also very good, and I’ve read the first and second Chronicles several times. The story and characters had such an impact on me that my wedding ring is made of white gold (Thomas Covenant’s white gold wedding ring is a fundamental element of the tale).

Unfortunately, I didn’t like The Last Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, and I just pretend they don’t exist. Maybe I’ll read them again one day and see if I change my mind.

Anyway, in The Wounded Land, the first book of The Second Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, Thomas Covenant says to another primary character,

That line stuck with me, and I wanted to write something based on the words “something broken,” which is how this poem came about. Despite its flaws, it’s one of my favorite poems that I have written. I was quite passionate about it, and I think it turned out pretty well. I also call it my “D” poem, becausemany of the words start with D. (Get it? GET IT?!)

My “Something Broken” isn’t about a man who’s lost everything, but rather about someone who is continually making poor choices without regard to consequence. It was written from an LDS perspective—as I mentioned some time ago in the commentary for Stormy Weather,

The subject of Something Broken—the friend—has taken this path and is beginning to suffer the consequences:

But now that he’s lost, he doesn’t see a possible way back and is contemplating suicide as a plausible “out.” This is evidenced by wandering the rooftop alone, and (maybe my favorite lines from the poem):

In this case, suicide is not the way out, it’s just furthering the devil’s victory, but that isn’t easy to realize.

The speaker of the poem hasn’t given up on him, though. One interpretation of the speaker’s identity is Jesus, though really it could be anyone. The line

Seems to me like it could easily be misinterpreted. It’s not that the speaker will give up on his friend, becoming an enemy; rather the lost soul will feel so uncomfortable in his presence that it will simply feel that way to him.

The superficial “something broken” is finally revealed in the final line. The “broken crown” represents the promised reward from Satan that is ultimately worthless. However, the real “something broken” is the lost soul. But the speaker understands that he can come back, and it may be hard, but worth it.

Setting aside the LDS view (since I no longer subscribe), I think it works well enough as cautionary tale of downward spiral. And though I wrote this a few years before The Lord of the Rings movies were released, the line

Now reminds me of something Sam says to Frodo as they lay shivering in Mordor, near the end of The Return of the King. Sam looks up at the sky and sees a brief break in the clouds, and says,

Tolkien’s original text is even better:

The light may be hidden from us at times, but it is always there, waiting to be rediscovered.

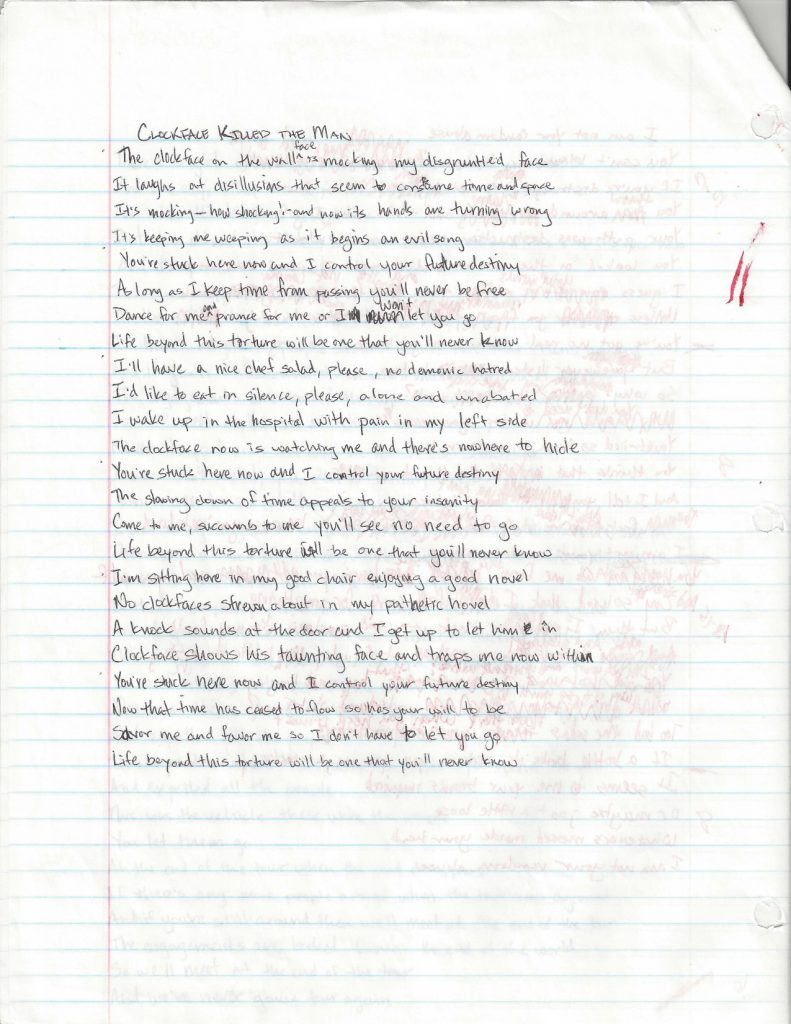

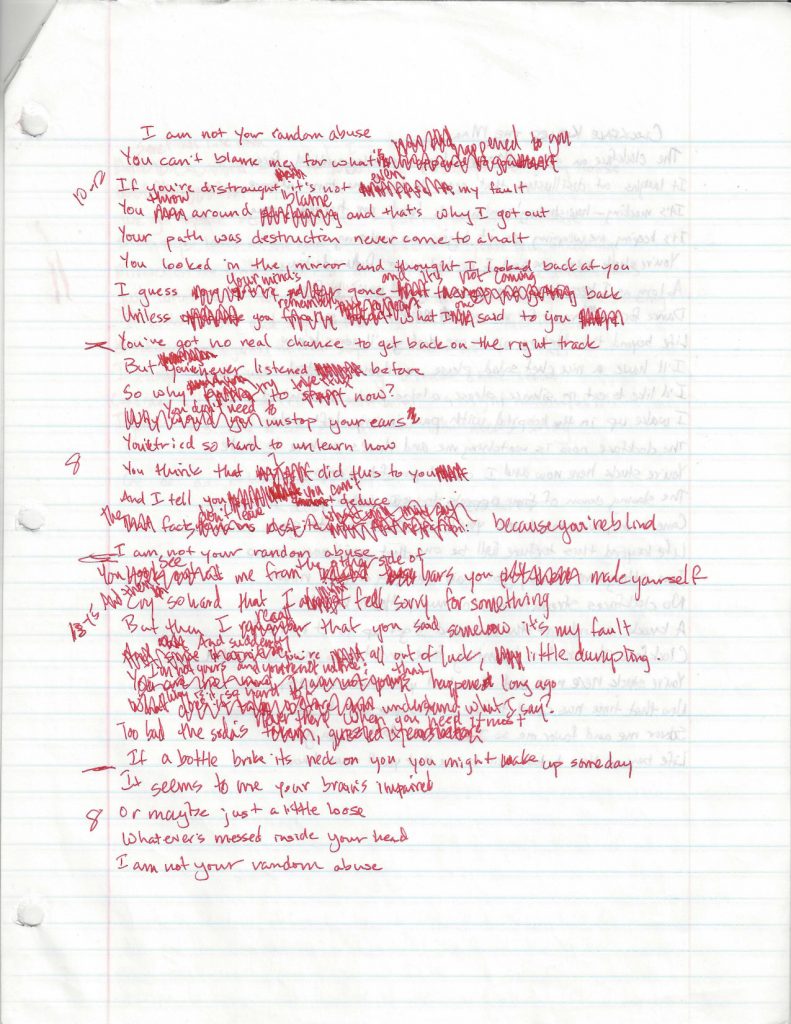

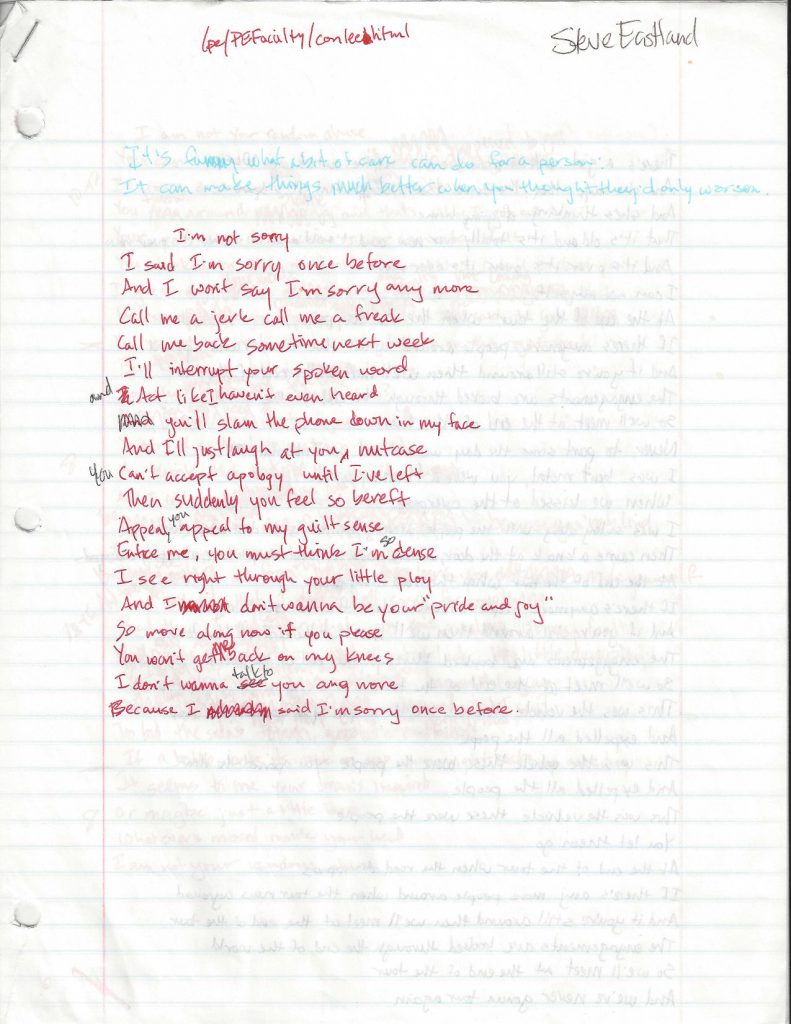

Some notes on the original handwritten version, seen below:

The scribbled-out “D’s poem” at the top refers to two different things. Firstly, as mentioned earlier, I call this my “D” poem, but I also have a friend who has a sister whose name begins with “D.” People often called her “D” in lieu of her name. Around the time I wrote this poem, she was also at BYU, and I would often see her around the time of my HEPE class, as it was in the same building as the university swimming pools, and she was a swimmer who apparently practiced around that time.

Next, I can’t decipher all of them, but some of the scribbled-out lines are:

I think we can all agree those lines are terrible. A few of the revised lines from the made it to the printed copy from my old web site, before becoming the final published version:

They are better, but I definitely prefer the final version. And as a final note, although Something Broken will remain as currently published, I offer the following replacement for the final line: